The iconography of The Christ

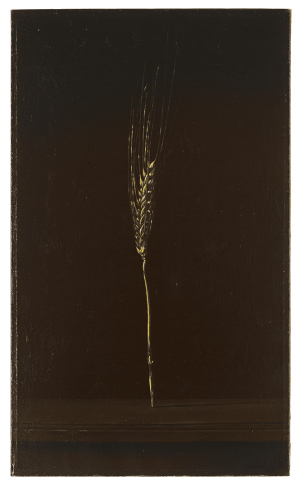

Dalí surprised the public and critics with his 1945 exhibition at the Bignou Gallery in New York, Recent Paintings of Salvador Dalí, when, in showing his most recent paintings, he presented two very different lines of work: the graphic embodiment of his interest in nuclear physics, on the one hand, and on the other, the thesis, announced in 1941, of his desire to become a classic. It was at this time, in 1945, that he painted The Basket of Bread[1], one of the most representative works of this period. In terms of technique and texture, it reminiscent not only of The Christ but also of the 1947 Saint George and the Dragon Killer[2], which, in spite of the title, depicts an ear of wheat.

Wheat, bread and Christ all symbolise the vital transition of the son of God, the passion and the future resurrection which the Catholic liturgy celebrates with the communion. In the words of the painter: “In artistic texture and technique, I painted the Christ of St. John of the Cross, in the manner in which I had already painted my Basket of Bread, which, even then, more or less unconsciously, represented the Eucharist for me”[3].

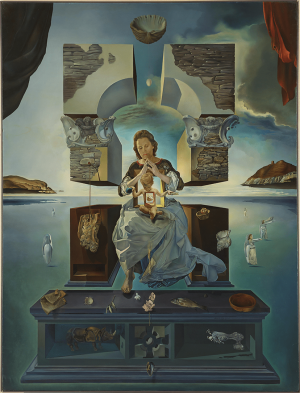

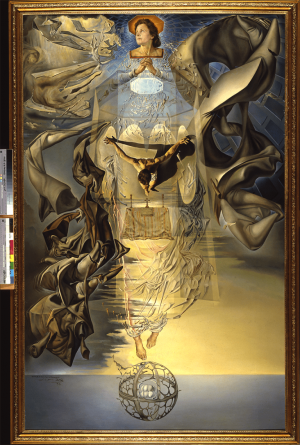

Having previously painted the Virgin on two occasions[4][5], Dalí began work on the representation of Christ at the same time as the publication, also in 1951, of his Mystical Manifesto, the starting point of the conceptual framework on which his painting of this period, the nuclear mystical, is centred. This appears again on at least two other occasions, the first being Lapis Lazuline Corpuscular Assumpta, from 1952[6], where we contemplate Christ as Madonna-Gala’s guide in the ascension of the Virgin. In the second, the figure is part of the iconography that accompanies Christopher Columbus[7] in the discovery of America, in a painting from 1958.

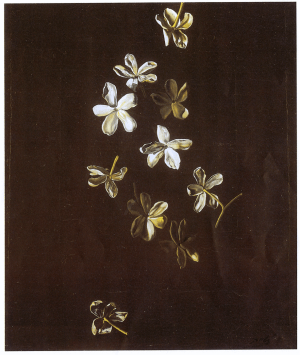

When Dalí wrote about the unusual position of his Christ, in a letter printed in the Scottish Art Review, he explained why, unlike other representations of the crucifixion, his was to manifest “the metaphysical beauty of Christ-God”[8]. At the same time, the painter confesses that he intended at first to include all the attributes of the Crucifixion and to transform the blood into red carnations, in addition to which three jasmine flowers would spring from the wound in the side. However, as we have said, the artist changed his mind; but he did not abandon the idea, as can be seen in these three paintings, made between 1950 and 1954[9][10][11].

Carme Ruiz

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, num. P607.

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, num. P.639.

-

Salvador Dalí, “A letter from Salvador Dalí”, The Scottish Art Review, vol. IV, no. 1, 1952, Glasgow, p. 5.

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, num. P643.

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, num. P660.

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, num. P670.

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, num. P743.

-

Ibid.

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, num. P658.

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, num. P657.

-

Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí, num. P772.