The Creative Process

To Draw Ideas, To Draw Thought, To Think The Christ

“But I must leave off here on the subject of drawing, which deserves a treatise by itself. Remember only that the whole lofty morality of your work depends on knowing how to draw well, and that Mr. Ingres wished to inculcate into you deeply this patrician idea, engraving it with the sharp point of his severe and juridical pencil when he wrote, in order that you should always remember it, that “drawing is the probity of art”[1]

Salvador Dalí, 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship (1948)

In the history of art, drawing is held to be the first of all the arts, both as an intellectual activity and as a universal language. Bruce Nauman was reprising Leonardo da Vinci’s idea of painting as “una cosa mentale” (“a thing of the mind”[2]) when he declared that “drawing is equivalent to thinking. Some drawings are made with the same intention as writing: they are notes that we do”[3].

Drawings are the testimony of an artist’s creative process, the first manifestation of the work, the first note of the idea or project that the artist has in mind; for this reason, their succession in a sketchbook makes it possible to observe their creator’s thoughts about the work, as well as their working process (conceptualisation), as if this were a brainstorm: the trying out of forms, the placing of elements, different compositions and so on. The Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí conserves a great number of drawings and sketch books, which clearly reveal the graphic ideas and thoughts for various paintings and projects, which give a lot of information about the artist’s working method in the study of his works.

For the exhibition Dalí. The Christ of Portlligat, which takes place at the Dalí Theatre-Museum, we have chosen the sketchbook from the Pere Vehí Archive in Cadaqués, which contains drawings and annotations that coincide with the beginnings of Salvador Dalí’s nuclear mystical period, the first formal manifestation of which was the publication of his Mystic Manifesto in 1951. In this sketchbook, the artist expressed in drawings and notes his thoughts about the various paintings and projects on which he was working, from annotations of the graphic script of the unmade film The Soul (1948-1952) to sketches for Christopher Columbus (1958), thanks to which the sketchbook can be dated to the years 1948 to 1958. We also find here, among other things, notes for the house in Portlligat relating to the extension that was carried out from 1949, as well as sketches for the staging of the photograph In Voluptate Mors (1951), taken by Philippe Halsman.

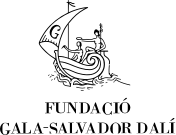

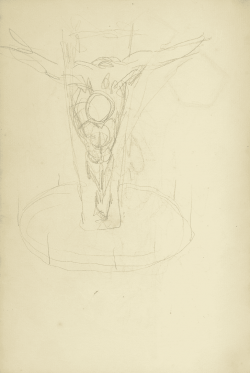

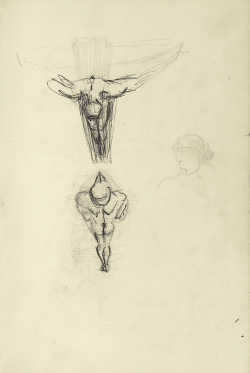

In addition, among these sketches and notes we also find Dalí's ideas for and thoughts about The Christ. These drawings reveal the artist’s process in creating this work and how he developed the idea of painting a Christ “as beautiful as the God that He is”[4]. We can follow the essaying of different compositions for the Christ, some of which recall the figure of Christ sketched by John of the Cross, although the great majority present the foreshortened floating figure in a frontal view, albeit with variations, such as the image of the reflected Christ.

Irene Civil and Laura Feliz

-

Nude Vibrations Dematerializing a Clothed Nude of Super-nude Vibrations, 1956

Num. Cat. P1176

Art Hispania, S. L., Barcelona

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2023

<

Nude Vibrations Dematerializing a Clothed Nude of Super-nude Vibrations, 1956

Num. Cat. P1176

Art Hispania, S. L., Barcelona

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2023

-

The Sacrament of the Last Supper, 1955

Num. Cat. P719

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Chester Dale Collection

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2023

<

The Sacrament of the Last Supper, 1955

Num. Cat. P719

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Chester Dale Collection

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2023

The Creative Process: Working Methods and Techniques

Dalí’s working process was intense. The artist reveals himself to be a tireless and meticulous worker who uses a richly varied range of technical resources to achieve the definitive painting. The idea for The Christ materialised in different phases, which bear witness to the flow of the artist’s thought in relation to the painting. First, Dalí made numerous sketches and drawings in different sketchbooks and on loose sheets of paper as visual notes of ideas for the composition of The Christ and its variants. In addition, in a separate phase, the artist looked at photographs and images in books, magazines and postcards for models to embody those ideas and initial sketches on the canvas. Finally, in a third phase, Dalí transferred the definitive models to the painting. This was an organic process, and one that, far from being innovative, was very much in keeping with the classical tradition, despite his always using his own options and others resulting from the use of the new materials and techniques of the time. This classical and at the same time updated tradition is collected by Dalí in his treatise on painting technique, 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship (1948), inspired, among others, by Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte. This book is a compendium of information on how the artist should live, on sources of inspiration, painting techniques, types of pigments and brushes and so on, as well as on the importance of drawing.

Irene Civil and Laura Feliz

Selected quotes from 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship:

Sketches and drawings as visual notes of ideas

A fundamental truth in your painter’s apprenticeship is that you must learn to draw before you even touch your brushes.

[p. 107]

Drawings of different subjects using different techniques

Sketchbook, Pere Vehí Archives. Cadaqués

[...] my Secret Number 20 [...]. The method of beginning to draw directly from nature and without the intermediary of pictures is the right one, and also that of working first from plaster casts after the antique before going over to the living models.

[p. 116]

Sketches of different figures using different techniques

Sketchbook, Pere Vehí Archives. Cadaqués

By the time you have acquired proficiency in drawing I advise you in turn to undress completely, for it is necessary for you to feel, as you are drawing, the design of your own body, as well as the august reality of the contact of your bare feet with the floor: for the man who knows how to draw and who, charcoal in hand, is able at last to draw what he wants, feels himself to become a kind of god [...]. Know this as Secret Number 23.

[p. 122]

Sketches of different figures with different techniques

Sketchbook, Pere Vehí Archives. Cadaqués

Remember only that the whole lofty morality of your work depends on knowing how to draw well, and that Mr. Ingres wished to inculcate into you deeply this patrician idea, engraving it with the sharp point of his severe and juridical pencil when he wrote, in order that you should always remember it, that “drawing is the probity of art”.

[p. 123]

Notes of Christ with different positions and compositions

Sketchbook, Pere Vehí Archives. Cadaqués

The search for the models

When you know how to draw, but only then, the use of snapshots in certain cases may be valuble to you. You msut realize that a camera is rigid and mechanical and your eye on the contrary is soft and full of an inventive whimsicality which the poor lens in no wise possesses.

[p. 122-123]

[...] this Secret Number 16 [...] you will voluntarily fall in love, madly in love, for the rest of your life, with the bit of landscape which you have already wisely decided, by your understanding, to be the one among all those that you love to be most worthy of all kind of sacrifices.

As your studio must be situated close to the spot where you were born, and as, if you are to be a good painter, this spot must be an admirable natural setting [...].

[p. 90]

A boat on the beach at Portlligat

The Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg (Florida)A Portlligat fisherman

The Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg (Florida)

Detail of the figure of the second fisherman in The Christ, 1951

Detail of the figure of the first fisherman in The Christ, 1951

[...] if you at last see again that landscape superposing itself on the landscape of your memory, so that they become like two identical crystals spheres which contain them, I warn you beforehand that if this vision made you drool the first time, today, twenty-seven years later, this same vision will not only make you drool again but it will also make you weep.

[p. 97]

Salvador Dalí on the beach at Portlligat, 1954

- Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2023

Image Rights of Salvador Dalí reserved Postcard with a view of the house at Portlligat

Different techniques for transferring the final models to the painting

Take the plan which is to be copied and place it on a sheet of paper of the same size as that of the original. [...] The two sheets being well joined and spread flat on a large carton placed on the table, one begins by pricking the angles or the points where the lines cross and cut one another upon the Plans.

[p. 109-110]

Set of black and white photographs of the model Russ Saunders (1) and blow-up detailing the punch transfer technique, with holes in the photograph and dots on the backing paper (2), resulting in the final transfer of the drawing using the technique described by Salvador Dalí (3).

Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres

The Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg (Florida)

Whichever manner you may use, after you have marked the points of the entire original work, you detach your copy, removing the pins or the pincers which you used to join these. And the sheet of paper being entirely covered with pin holes or impressions, one then draws from one point to another lines similar to those which are traced in the original. These lines are frist drawn with the pencil of which the point is so divided as to form a double line.

[p. 110]

Detail of the painting of The Christ and IR image of the same detail in which the marks of the technique used to transfer the underlying drawing are visible.

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow

© CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

[...] after you which you will transfer your tracing to it according to the following directions, which constitute Secret Number 24.

For this you will proceed as do the engravers to transfer their tracing to their copper plate. In other words, you will engrave your drawing by means of a needle or other extremely fine point on a sheet of cellophane of the right size. Then you will daub your tracing with oil paint, [...]. With the white and the burnt umber you will make a tint just sufficiently perceptible to enable you to see clearly the finest details of your tracing. This paint must be applied without any varnish or drier, so that your tint will penetrate the indentation of each line engraved in your cellophane. [...] you must even rewipe the whole two or three times with a flat buffer slightly moistened with ammonia in order to remove the oiliness which might remain on the surface. Having done this, you apply the face of your tracing to your panel laid out horizontally, and using an engraver’s roller you press it as you would to obtain a printing of an etching [...] until you obtain a complete transfer. This method is the only clean way of obtaining a perfect tracing of the most detailed drawing executed directly in oil paint [...].

[p. 124-125]

Left: Detail on the black and white photograph of the model Russ Saunders’ left hand.

Right: Sheet of cellophane with the hand marked out with a punch or a very fine sharp point.

Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres

Black and white photograph of the model Russ Saunders.

Sheet of cellophane with the figure in the photograph directly traced, in this case, in black ink.

Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres

Very good india ink in solid form diluted with water creates a gray which is very satisfactory for preparing the drawing on the panel, but as one cannot trace directly with this ink, you will first have to transfer your drawing with powdered lead and then go over every line with india ink [...].

[p. 125]

-

Salvador Dalí, 50 Secrets of Magic Craftmanship, Dial Press, New York, 1948, p. 123.

-

In Leonardo da Vinci, A Treatise on Painting, trans. John Francis Rigaud, Dover, Mineola (New York), 2005.

-

Bruce Nauman quoted in Juan José Gómez Molina (coord.), Las lecciones del dibujo, Cátedra, Madrid, 1995.

-

Salvador Dalí, “A letter from Salvador Dalí”, The Scottish Art Review, vol. IV, no. 1, 1952, Glasgow, p. 5.

Tracing in black ink of a figure from the Louis Le Nain painting, Paysans devant leur maison (Peasants Before Their House), 1641

Tracing in black ink of a figure from the Louis Le Nain painting, Paysans devant leur maison (Peasants Before Their House), 1641 Reverse of the tracing paper medium with the surface hatched over with graphite to enable the image to be transferred

Reverse of the tracing paper medium with the surface hatched over with graphite to enable the image to be transferred